UPDATE: Jan. 2015

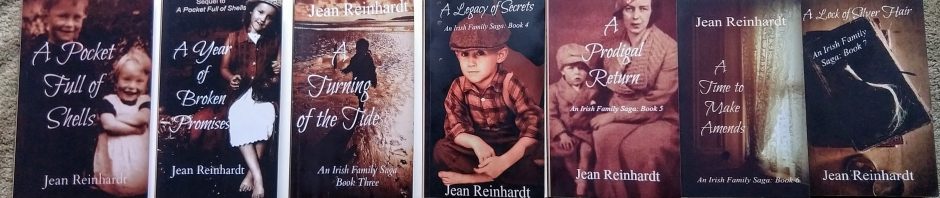

There has been a fantastic response to the launch of A Year of Broken Promises and I am very, very, grateful and appreciative of all you wonderful readers who have taken an interest in the sequel to A Pocket Full of Shells. The books are in first and second place of the top 100 paid in the Victorian Romance category on Amazon UK. I’m working on book three, A Turning of the Tide, which should be ready for publication in March/April.

This is the sequel to A Pocket Full of Shells

UPDATE on the sequel:

Hopefully the book launch will take place either first or second Saturday in December, in The Long Walk shopping center in Dundalk.

Hopefully the book launch will take place either first or second Saturday in December, in The Long Walk shopping center in Dundalk.

I’m leaving these first draft chapters up on the blog but I won’t post any more as I have almost finished the book and will be editing it soon. I have a few beta readers lined up and once it’s proofed I should be able to publish it by early December. It’s called ‘A Year of Broken Promises.’

If you have read A Pocket Full of Shells and would like to find out what happens next in the McGrothers’ lives, here are chapters 1 to 6 from the first draft of the sequel; A Year of Broken Promises.

The book should be available on Amazon by early December.

**************************************************************************************

Chapter One

James McGrother hung back from the grave, watching his uncle Pat’s old shoulders hunched against the wind as he knelt in prayer. Blessing himself quickly before chasing after his three young children, James knew that nothing he could say would lessen his uncle’s pain. It was better to leave the grieving man alone to speak the words in private that he never got the chance to say at the funeral. Earlier that morning, Pat told James that he could not face another night without talking to his beloved Annie and had asked his nephew to accompany him to the graveyard.

The young father guessed that his three children were playing hide and seek around the ruin of the old church in the center of Haggardstown cemetery. The only sound he could hear was the whistling of the wind through the gaps in the broken walls. When he eventually found them, Catherine was sitting on the ground, her arms around her two younger siblings. They were leaning against one of the cold, stone walls and seemed frozen to the spot. When they saw their father, Thomas aged nine, and his four year old sister Mary-Ann, ran screaming into his arms. James gathered them up and looked over at Catherine, who was smiling sweetly back at him.

“Has your big sister been frightening the life out of ye with her ghost stories again?”

“We made her tell us, Daddy. She said Annie had told her the same story when she was my age and it didn’t frighten her at all. Men don’t get scared, do they? Does that mean I’m not a man yet?” asked Thomas.

James saw tears well up in his son’s eyes and knelt down so their faces would be level with each other. He pulled his youngest child close to his chest as she was beginning to shiver, the cold wind biting at her. As he wrapped both sides of his jacket around Mary-Ann’s thin frame, James noticed that Catherine had joined Pat at the graveside.

“Of course you’re a man, Thomas. Aren’t you my little man? Soon you’ll be as big as me and then I won’t be able to call you that any more. And don’t ever be ashamed to say you’re scared. I’ve been scared many a time. Ask your mammy.”

James watched his daughter patting the hunched back of the old man who was like a grandfather to her. She rested her head on his shoulder until Pat laid a hand on the wooden cross that bore his wife’s name and hoisted himself up onto a pair of shaky legs. Looking behind to where his nephew stood waiting, the old man placed his cap back on his head and took hold of the small, cold hand held out to him.

“Is Mamó asleep now? Do you think she’s warm enough, Daddo?” asked Catherine.

“Aye, a stór. She’s in a deep sleep and cannot feel the chill of this breeze. Come on now, let’s get ye all back to the fire and warm up those poor frozen hands and feet,” said Pat.

As the men took one last look around the cemetery, Pat’s eyes came to rest on a plaque that bore the name of a young man.

“Annie lived to a good age, James. We both saw some hard times but if I joined her tomorrow, I have no regrets. We have lived a lot longer than some of these poor souls, like young Doctor Martin over there. Cut down by the fever in his prime he was, while tending the sick and the poor, bless him. He was barely a day over thirty.”

“I’m going to be a doctor when I grow up,” said Thomas.

James and Pat smiled at the boy who was standing as tall as he could manage, his chest thrust out. They both knew he would be a fisherman in a few years’ time. It was the way things were and they were not likely to change.

The wind had raced ahead to reach the cottage near the shore, where Mary McGrother lay in bed. She was not asleep, but her eyes remained closed as the door opened and a cold draught swept her children into a parlour that was not much warmer than the garden.

“Mary, wake up, you can’t sleep all day like this. The fire’s almost out and the place is freezing,” James scolded as he placed some bricks of turf onto the dying embers.

“Leave her be, son. Leave her be,” said Pat.

Chapter Two

Owen McGrother paid close attention, while his eldest daughter read the letter his brother James had sent from Ireland. It was his second time listening to the news being relayed to the rest of the family, gathered in the parlour of his house in Sunderland. Owen placed an arm around the shoulders of his wife Rose, as she sniffed back fresh tears.

“Annie will be sorely missed with a baby on the way and three other wee ones to take care of,” said his brother, Peter.

“That’s not the worst of it. Read on love,” said Rose.

‘We are all missing Aunt Annie and none more so than Uncle Pat. But the one I am more worried about is Mary, she is acting very strangely indeed and has not shed a tear for the woman who has been like a mother to her for more than ten years. She sleeps most of the day and young Catherine is the one looking after the house when myself and Pat are not here. She is not getting to school because of it. I’m sorry to impose by asking for help and I will understand if the answer is no.’

The young girl stopped reading to look at her aunt Maggie.

‘Can Maggie please come and help us out, just until the baby arrives. I think that once Mary has the wee one in her arms it will bring her back to us. Please write back soon. If Maggie can come I might be able to go over to ye and work in the quarry, if there are any jobs to be had, as there is very little to be got here. Pat sends his love to all of ye and your wee ones. Your brother, James.’

The room was silent as all eyes turned to Maggie. She shifted in her seat, her mind already made up as to what she would do.

“Well now, all my lot are big and bold enough to take care of themselves. I know wee Jamie comes to my house after work but another hour waiting for a meal from his mother won’t kill him, will it Rose?” it was more of a statement than a question.

“Of course it won’t. James and Mary need you over there. Remember how you nursed him when he had the melancholia the first time he came over? He needs his big sister to do the same now for his wife. We can help you with the fare and if James comes here he can stay in your house. I’ll make sure they all get fed, so you needn’t worry about that, Maggie,” Rose meant every word.

A letter was immediately written and posted to James the following day.

Chapter Three

A dribble of the broth that Catherine was trying to feed her mother slid down Mary’s chin. Neither of them seemed to notice so James took the bowl from his daughter and said she could go play outside with her brother and sister. Catherine quickly left the house, grateful to her father for taking over a task that had, of late, rested mostly on her young shoulders.

“Come on now, love,” coaxed James, wiping his wife’s mouth, “You need to keep your strength up. I know where you are, Mary. Surely you remember the time I was there myself. It is not a place I would wish on my worst enemy. Come back to us, please. The children need you – I need you.”

James looked into the vacant eyes of his young wife. Pat had taken to leaving the house early in the morning as he could no longer stand to see her wasting away in front of them. The neighbours had stopped calling and even their children rarely played around the house as they used to. A quick knock on the door and a shout for the McGrother children to join them was the nearest thing to a visit the cottage had received for almost a week, as Mary slowly withdrew more and more each day.

A thousand thoughts and what ifs raced through James’s head. What if he had been home when Annie passed away? What if he had stayed in Ireland, instead of spending the last few months in England? They had needed the money, especially with a fourth child on the way. Nobody could blame a father for wanting to look out for his family, for doing his best to provide for them. James was sure that Mary knew how much he wanted to remain at home, fishing and taking work in the harvesting when it was available.

“Surely you can’t be blaming me, Mary. Mary. MARY,” James shouted, hoping to snap her out of her trance.

Catherine ran in from the garden. She had been hovering near the door in case she was needed and heard the shout. Standing in the middle of the parlour she saw tears run down her father’s face. She could not recall him ever raising his voice in temper to anyone. Not even to his children on their worst behaviour. It was her mother who disciplined them and Catherine remembered plenty of times when she felt the sting of her quick hand across the back of her legs.

“Daddy. Daddy,” Catherine spoke just above a whisper.

James slowly turned his head towards his eldest child. The look on her face jolted him out of his frustration and he was by her side in two strides, sweeping her up into his arms.

“I was just trying to get your mammy’s attention, love, I’m not mad at her. She’s a little bit lost right now, let’s give her some more time, eh?”

With her finger, Catherine traced a wet streak that ran down her father’s cheek and into his clipped beard.

“I know, Daddy. I don’t mind looking after her until she’s better. I’m a big girl now. Aren’t I?”

“That you are, girl. That you are. Will you be able to cook that rabbit Pat has skinned, or will I stay and help?”

Catherine felt all grown up shooing her father away out the door to go tend the nets with his uncle and the other fishermen. The wind was calming down and she knew they would be out in the bay that night. Passing by her mother’s bed on her way to the fire, she patted the top of her tangled hair. It had been a week since Mary had let anyone near her with a comb and Catherine made a mental note to try again later that evening. One glance out through the tiny window told the young girl her siblings were engrossed in a game of hide and seek with their friends. It wouldn’t be long till they were in looking for food so she hurried on with preparing the rabbit, rubbing in the herbs that she had gathered that morning, just as Annie had shown her many a time.

As the men silently worked on their nets, Pat glanced at his nephew. James was one of the few men left in Blackrock who had held onto his boat. Some had sold their vessels to feed their families and others had grown too old or too sick to carry on. Hundreds of young people had emigrated from the parish to join family and friends in England, many of them making their way to America from there. They were no longer satisfied with the seasonal work of agricultural labouring or the erratic earnings from fishing, which was always at the mercy of the weather.

“What’s on your mind, James? You’ve been very quiet all day.”

“Sure aren’t I always quiet. You’re not so talkative yourself, Pat.”

“Aye, that’s true enough, but I don’t usually notice the silence lying between us. Today, it feels like a stone wall. Is it Mary you’re worrying about? Give her time, she’ll be right as rain when the baby comes.”

“It’s not just Mary. Besides, Maggie will probably come over and help us out. I’m sure of it,” James couldn’t look his uncle in the eye and kept his head down as he spoke. “I’m thinking I might have to sell the boat.”

The older man stopped what he was doing and stood up, staring in disbelief at his nephew, who carried on mending the nets. James could feel the eyes of his uncle on him and was beginning to regret divulging the thoughts that had been tormenting him. Pat was trying to remember the last time he felt so outraged.

“The only other time I remember roaring at someone was when Annie sold her two lovely bowls to raise money for Mary’s trip to England, that time you were sick. That was quite a few years ago and I’ll admit, I did let a roar out of me. I never saw Annie jump like she did, it almost made me laugh,” said Pat.

“Well, you can spare me the roar. I can tell you’re not too happy about what I said,” James put the net down and looked up at his uncle. “You know that selling this boat is the last thing I want to do but there’s work with my brothers in England and every time I spend a few months over, I earn enough to keep a roof over our heads for a good six months. What’s the point in holding onto the boat for the seldom it’s used anymore?”

“Maybe you shouldn’t stay so long away then. You were in England when Mary lost her baby last year and you were there when Annie passed away. We can manage with the fishing and a bit of labouring. I still have some life left in me, don’t I? Or am I not needed anymore, like your boat, James?”

The younger man was cut to the heart by his uncle’s words. He was torn between what he wanted to do and what he needed to do. He had gotten a good run from his boat and it was in fine condition.

“It might not even sell, Pat. It’s just something I was considering. Let’s leave it for now. I’m sorry about not being here for Annie but even you didn’t know she was sick till the night she died. If I’d had more warning you know I would have come back straight away.”

“I’m sorry James. What I said was uncalled for, you don’t need me making it harder for you. Myself and Annie were never blessed with our own children, so I’ve not had the same worries as you, son, with just the two of us to provide for. I’m in no position to give advice and you don’t have to listen to the ramblings of an old man. You must decide what’s best for your family and you will have my blessings on whatever that may be.”

The children were asleep in the tiny room above the fireplace. They had gone to bed clutching the presents Maggie brought with her from England. All except Catherine, who had been trying to comb her mother’s hair, intent on weaving into it, one of the pretty ribbons her aunt had given to her.

“Let me do that, Catherine. Go on up to your bed and have a good night’s sleep so you’ll be fresh as a daisy in the morning for school.”

“Can’t I stay home with you, Auntie Maggie? I don’t need to go to school anymore, I can read and write well enough now.”

“Your father wants you to stay because he left too young himself. Me and my sister would drag him to school until he was eight years old. After that, he got too big and we couldn’t carry him. So we would leave him lying in the road because he was making us late for our work up at the big house. He wanted to be with his brothers, out working in the fields and on the farm. As he was the only one in the family who could read, your father felt he had done all the learning he needed and was ready to leave school.”

“He never told us that,” whispered Catherine.

Maggie looked around the cottage. The men were out fishing and the only other person in the room was Mary, who had not even acknowledged the fact that she had a visitor. It was the perfect opportunity to spend time alone with her sister-in-law.

“That’s because he wants you to finish school, my love, even if some of your friends don’t,” Maggie spoke in the hushed tone of a shared secret. “Your father tells me you already write better than he can. Now don’t tell him I told you that. He was always a good reader but struggled with his writing. Sure you only have half a year left to go, that’s not long at all. All of your cousins across the water finished school, some of them even got apprenticeships.”

Catherine didn’t know what ‘apprenticeships’ meant but it sound very important to her. She figured a word that long was something to be either ashamed or proud of. The beaming smile on her aunt’s face told her it was the latter.

“All right so. I’ll leave you to look after Mammy. Maybe she’ll let you comb the knots out of her hair, she’s being good tonight,” Catherine kissed the top of her mother’s head and hugged her aunt.

When they were alone in the parlour, Maggie took her niece’s place at the side of the bed and began combing Mary’s long wavy hair. There was no response from the younger woman and it took all of Maggie’s patience to hold back from grabbing her by the shoulders and shaking her. It had been the same with James. They had all tried to bring him back to them by coaxing, shouting, even slapping him, to no avail. His sisters had cried in front of him and he never once reached out. It was Mary’s visit and the handful of shells his little girl sent over, that finally broke through the invisible wall he had managed to build around himself. Maggie knew she would have to find a way to do the same with Mary, as quickly as possible, before the young woman got too used to her presence.

There was a song that Maggie’s mother used to sing to her children as they went to sleep. Maggie often sang it to her own young ones when they were smaller and it was the same piece of music her brother Peter played on his fiddle at the end of family gatherings. She closed her eyes, remembering what it was like lying with her brothers and sisters, listening to the song as they drifted off to sleep. Even the animals at the other end of the cottage would settle down for the night at the soft tones of her mother’s voice.

As she gently untangled Mary’s hair, Maggie sang ‘The Parting Glass.’

‘Oh all the money that e’er I had

I spent it in good company,

and all the harm that e’er I’ve done

alas, it was to none but me.

For all I’ve done for want of wit

to memory now I can’t recall.

So fill to me the parting glass,

goodnight and joy be with you all.‘

As the verse came to an end, Mary crossed her arms over her stomach and curled up in a ball. The comb was caught in her hair and as Maggie was trying to untangle it she heard a soft low moan. It seemed to be coming from across the room and she peered into the dim light, cast by the fire’s dying flames. Thinking that one of the children had crept down the stairs and was hiding in the shadows, Maggie called out in a loud whisper.

“Which of ye is hiding in the corner? Get back up to your bed this minute, do you hear me?”

Mary was still lying in a fetal position and Maggie realized where the sound she could hear was coming from. Leaving the comb stuck in the long tresses, she leaned over the younger woman and wrapped her two arms around her, pulling her up into a sitting position. The two women rocked backward and forward as the song filled the air once more. Huge sobs now broke free from Mary’s body, drowning out Maggie’s voice and alerting the children overhead that something was wrong.

Catherine and her younger siblings were shocked at the scene that met their eyes at the bottom of the stairs. Their mother was creening and sobbing and their aunt had her clasped in her arms as she sang to her. Both women were slowly rocking to the rhythm of the tune. The children sat on the bottom steps and waited anxiously for the singing and crying to come to an end. Gradually, Mary’s sobs quietened and Maggie’s voice trailed off as the rocking stopped.

“Mary, are you back with us now?” whispered Maggie.

The young mother didn’t reply. Instead she turned to look at her three frightened children on the stairs and held her arms out to them. They immediately ran to her, sobbing. After a while, when everyone’s strength was spent from crying, Mary kissed her children and sent them back up to bed, promising to make breakfast for them the following morning, before they set off for school.

“Do you want me to go up with ye?” asked Maggie.

“We’ll be grand, Auntie Maggie, sure haven’t I been bringing these wee ones to bed for years now?” said Catherine as she pulled her little sister along by the hand.

“I can go to bed by meself so I can,” sulked Thomas, ashamed off his swollen red eyes.

“Of course you can, son,” said his mother. “Catherine, you settle Mary-Anne while Thomas gets to sleep. You know what men are like if they don’t get their rest.”

“I do, Mammy. They wake up with faces on them that would sour milk, don’t they?” said Catherine.

Thomas didn’t care about the disparaging remark from his older sister. His mother had called him a man and that was enough to add two inches to his height as he climbed the stairs.

As soon as they were alone once more, the two women clung to each other and cried fresh tears.

“What brought you back to us, Mary? Was it the song?”

“Oh Maggie, that was my father’s favourite song. He would get my mother to sing it while he played the tune on his fiddle. It was the last song she ever sang. After my father sold it to pay our rent my mother swore she would never sing again and she kept her word, until the day he left to look for work in Leitrim. He kissed us wee ones goodbye and I watched as my mother took his hand and walked him to the end of the village. I ran around the back of the houses and hid behind a hedge, trying to get as close as I could. She held both of his hands and sang “The Parting Glass” to him. That was the last I saw of my father. I never found out what happened to him but I know in my heart he’s dead and most likely buried in a pauper’s grave,” tears streamed down Mary’s face as she spoke.

Maggie was wondering just how much of the previous two weeks her sister-in-law was aware of. She was afraid to say something that might send the young woman back into the depths of despair.

“Do you remember what happened to Annie?” asked Maggie.

“I do, but I couldn’t cry or let myself feel anything. It was as if my heart had turned to stone. I’ve been aware of James and Pat talking to me and poor Catherine looking after me as if I was a baby. I was afraid to let go, Maggie. It felt as if the loss of my parents, and my younger brother and sisters being brought to America, was all rolled into one. I thought that if I was to grieve for Annie then it would open a floodgate that I might never be able to close. Does that make any sense to you at all?”

Mary’s sister-in-law brought her some hot tea that had just been brewed and reassured her that what she had experienced was normal for a pregnant women who had lost so many loved ones.

“I went to see someone in the workhouse back home – just the once, mind you. The old man who used to live across the street from Owen and Rose, remember him?” asked Maggie.

Mary replied that she did, as the image of his thin, crooked frame came to mind.

“Well, the poor old soul spent his last months in there. I saw a lot of unfortunate women in that place with the same look on their faces as you wore, Mary. Many of them had lost husbands and children and had just given up on life. I always meant to go back and pay some of them a visit, but I couldn’t bear to step foot inside the place. Not even one more time. The dark places that exist inside our heads are just waiting for us to enter. Once you go in, it can be very hard to leave. The longer you stay there, the less likely you are to escape. Promise me, Mary, that you will never go back, no matter how bad things get. Will you do that for me, love?”

As Mary nodded her head the comb swung across her face and she pulled it out from the tangled mass of hair. Maggie took it from her and climbed onto the bed behind the young woman. Pulling the wooden teeth through the knots she hummed the tune that had played such a big part in Mary’s recovery. When the job was done both women lay down side by side, falling asleep with a blanket draped across themselves.

James arrived home with Pat in the early hours of the morning and knew, as soon as he saw the peaceful expression on his wife’s face, that Maggie had worked her magic.

Chapter Five

The tension that had existed between the two McGrother men dissipated as soon as James swore an oath to his uncle that he would put off selling his boat for one more year. As the crew of four dragged the vessel along the compacted sand, their wives and daughters gathered to gut and clean the fish. Maggie had turned up in place of Mary and James burst out laughing when he saw her waiting with a wicker creel at her feet.

“And just what is it that you find so amusing?” she asked, hands on her hips.

“Maggie, I’m sorry for laughing. But you can’t seriously hope to carry a heavy creel of fish the two miles to Dundalk. You’ve grown soft in England these past ten years. The longest distance you have carried anything would be the washing to the clothesline in your back yard – and you’re not getting any younger either.”

The crowd around them laughed out loud as they carried on with their work. Maggie wasn’t sure which infuriated her more, her brother’s remarks about her fitness or her age.

“Here, Pat, throw me over those fish you are cleaning and I’ll wash them,” she said. “Anyone would think I was a gormless fool, the way my wee brother talks to me,” emphasizing the wee for the benefit of the audience.

When the fish were all cleaned and packed into the wicker baskets each of the women picked one up and headed for the road. James and Maggie were the last two on the beach, Pat and the rest of the men making a hasty retreat. They both reached for the creel at the same time and James got it first. Maggie tried to pull it from him and a tug of war developed between them.

“James, do you mean to walk like a fishwife into town, making a show of yourself?”

“Maggie, who do think has been bringing the fish in these past two weeks?”

“Well then, why don’t we go together? You can take it from me if you see me stagger,” Maggie was half relieved for his offer. She wasn’t sure she would be able to keep up with the other women.

“I’m only thinking of meself, Maggie. Sure by the time you arrive the fish will have tainted and nobody would buy it. The other women would be home and in bed and… oww… that hurt,” James rubbed his shin where she had kicked him.

The journey to Dundalk was a mix of pleasure and pain. Pleasure for James to reminisce with his older sister on memories of their childhood in Monaghan. Pain on Maggie’s part because she stubbornly refused to hand over the heavy creel to her brother until her back felt like it was broken.

Early next morning, after another good night’s fishing, James was surprised to see Mary and Catherine waiting for them on the shore.

“Where’s Maggie?”

“Ah, James. The poor woman could hardly stand up straight last night. Tis worse she’ll be today, sure I couldn’t bring meself to wake her,” said Mary. “Young Catherine here will be a great help, won’t you?”

The young girl smiled at her father and hoped he wouldn’t mention the fact that it was a school day. Thomas was helping the men with their nets while Mary-Ann picked up a fish every now and then to give it a kiss. She apologized to each one for her father taking them away from their watery home. That always got a laugh out of the adults busy preparing the catch for market.

“I suppose it won’t do any harm to miss one more day of learning, you go with your mammy so. I’ll make sure Thomas sets out in good time. Monday morning it’s back to school for the week, my girl. Do you hear me?” James used his sternest voice.

Catherine nodded her head and picked up the small creel that Pat had made for her. She always went to Dundalk on Saturday mornings with her mother, even if there was no fish to sell. Going there on a school day made it even more enjoyable. Sometimes they sold herbs from the plants in the garden, or berries when they were in season, making up for any lack of fish. Catherine loved the buzz of the town and the various sounds it produced. She suspected her mother did too, even though she complained about the crowds and the noise to the family on their return home.

There was a larger than usual gathering of people on the quayside that morning and Catherine asked her mother why so many of them were crying.

“That’s Vere Foster’s girls being sent to America. He thinks he’s doing them a favour. Even though he means well, not all of them young ones will end up in good employment, mark my words,” replied Mary.

“Is that the man Daddy says is always taking young girls away?”

“He is, Catherine, and mind you don’t get any fancy ideas in your head about following them. There’s many a story about bad things happening to those girls and before they even get off the ship at that.”

As they walked back home with the other women, Catherine thought about what her mother had said. Even though her parents were against so many young people leaving home she had heard others talk about the great life that was waiting for them in America. She wondered what it would be like to sail on a boat so much bigger than her father’s and secretly vowed that one day she would find out.

The Wreck of the Mary Stoddart

The Wreck of the Mary Stoddart

Chapter Six

Young Thomas McGrother sat on the floor near the fire, sulking. He was in no form to play outside with his siblings and their friends. Mary noticed how quiet her son had become and left Maggie to settle the latest arrival to the family.

“What ails you, son? You’ve been sourly all week. You should be out in the fresh spring air with your sisters,” said Mary.

“Why do you keep having girls, don’t you and Daddy like boys anymore?” Thomas immediately regretted speaking out, afraid of what the answer might be.

Mary tried not to laugh. Her son was clearly not impressed by the arrival of his little sister, Brigid, but she felt relieved at the reason he gave for his sullenness. The fact that she and her husband had been through bouts of depression made her worry that they might have passed something on to their children. Mary knew of families where that had been the case.

“Ahh, son. Is that all that’s bothering you? We have to accept what God gives us, it’s he who decides whether we have a boy or a girl. Sure he must think you’re a great fella altogether, helping your father look after a house full of women, if he sent us another girl.”

Thomas’s face brightened a little, “I would have liked a brother, Mammy. Could you ask God to send us one next time?”

Mary assured him that she would pray hard for his wish to be fulfilled.

“Go on now, off with you. There’s talk of a bad storm coming and we could be shut up in the house tomorrow, so make the most of a dry day.”

Maggie smiled at the conversation she had just overheard. The baby was asleep and it wouldn’t be long before the men returned from work. James was known for building a good wall, he had learned a lot from helping Mary’s father, a stonemason, when they lived in Monaghan. Whenever he was asked to repair some old walls, even though the pay was only for one man’s work, James would asked his Uncle Pat to help him with the job.

Ever since Annie had passed away, Pat had seemed lost and James would often find him looking into the distance. He seemed to be searching for something but when questioned, Pat would blink and shake his head and the faraway look in his eyes would be gone. It was as they were returning home, having spent the day working at one of the big estate houses, that James decided to broach the subject of his uncle’s absentmindedness.

“Have you been listening to a word I’ve said, or are you off daydreaming again?” asked James.

“Watch your tongue and show a bit of respect. Daydreaming’s for women. Did you ever think that I might just want a bit of peace and quiet now and then and it’s easier for me to turn a deaf ear than tell you to close that gob of yours?”

It wasn’t the words his uncle spoke that stopped James in his tracks, but the tone of his voice. As he stood watching Pat stride ahead of him he began to think he had imagined the harshness and irritation that had come out of the normally kind and soft spoken man. A chilling breeze came from nowhere and whipped around the young fisherman. James ran to catch up with his uncle, who had kept up his fast pace and not once looked back at him.

“The wind is starting to bite, Pat, would you not put your jacket on?”

“You’re getting soft in your old age, son. You need to spend more time out on that boat of yours and toughen up a bit,” replied Pat in a much friendlier voice.

The older man adjusted his rolled up jacket, wedged securely under his armpit. James pulled his own tightly around him to keep out the cold draft forcing its way under his loosely fitting clothes. Noting the extra space inside his jacket, James realized he had lost a fair bit of weight over the winter. He was a man of slim build and couldn’t afford to drop too many pounds without appearing gaunt. In a line up for work, only the strongest and healthiest looking men were chosen and James had spent the winter at home instead of taking up the work his brothers had found him in England. He needed to take whatever he could get in the line of work but this meant that he sometimes missed going out on his boat when the fishing was good. His crew would take it into the bay without him and although he got a small share of the catch, it wasn’t enough to sell.

Money was scarce with an extra adult to feed and James had caught Maggie putting food from her plate onto his wife’s when she wasn’t looking. When he confronted his sister about it she told him Mary needed it more, with a baby at the breast. “Besides, it doesn’t do for a middle aged widow to carry too much weight on her. Some handsome prospect might be put off asking for my hand if I’m not careful,” Maggie had joked.

By the time Pat and James reached the cottage the wind was blowing a gale. The women had brought the hens in early and locked them into their coop, under the large wooden dresser that Pat had made for Annie many years before. As he passed it by, he ran his fingers over one of the smooth wooden bowls that had been his wife’s pride and joy. A flash of anger surged through Pat at the thought of Annie being forced to sell two of them, but in an instant the feeling was gone and the increased pitch of the wind outside caught his attention.

“There will be no fishing for a while, James, that storm is settling in, mark my words.”

“I think you’re right Pat, it was good that we got that last bit of work.”

As the family sat around the table, talking to each other above the howling wind, they had no way of knowing just how prophetic Pat’s words had been.

This is a absolutely beautiful story even better than the first one if that is possible, it is

very well written and left me wanting to read more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for such an encouraging comment, Brenda. I’ll have two more chapters posted next Wednesday.

LikeLike