Seamus O’Sullivan wiped a tear from his cheek as he looked in from the street, through a grubby window, at a young man chastising his child. No one else in the crowded cafe paid any attention to the conversation between father and son. Each person’s face wore its own mask, covering its own sorrow. Seamus was no longer able to hide his emotions as tears continued to flow into the two day old stubble on his chin. He remembered how much he had chastised his own son, which turned into a thirty year dirge. One that now haunted him. He should never have remarked on the boy’s clumsiness, or let it be known how much the softness in his son irritated the hell out of him.

The young father knelt down to wrap forgiving arms around his sullen child. Seamus looked with longing at the compassion and gentleness being displayed in front of the cafe’s unobservant clientele. The times he held out a rigid hand for his son to shake – instead of embracing him tightly, snugly, safely in his arms – came rushing back accusingly from the past. Seamus crossed the street to where a collage of colourful boats tossed and turned in the fitful waters of a winter’s tide. As he was about to fix his cap more securely on his head, an icy gust of wind snatched it, carrying it out over the harbour.

Seamus instinctively pulled the collar of his jacket around his ears. He watched the rise and fall of his cap through the air as if invisible pranksters were throwing it from one to the other, taunting him, like school yard bullies. Old familiar but unwanted feelings began to surge through his body. Memories of an anxious childhood came flooding back.

One particular event stood out from the rest of his boyhood bullying. A cap his father’s brother had given to Seamus as a present on a visit home from America had become a prized possession. It bore the logo of a basketball team and each time it was worn, people would remember the good fortune of his uncle. They would remark on how well he had done for himself, one of their own, a big time business man in the States. Seamus’s father would puff up with pride at the compliments paid to a member of his family, as if he himself were the recipient of such praise and commendation.

Seamus the man, knew it was only a cap and not a big deal. The lads were just having a bit of fun at his expense. Seamus the boy, had felt intimidated, helpless, unable and unwilling to chase after them. It was not the mocking laughter, fading into the distance with his cap, that left a lasting mark on him. Nor was it the sharp clip on the back of the head his mother gave him, when he arrived home from school without it. What Seamus could never erase from his memory was the look of disgust on his father’s face across the dinner table, when his mother announced yet another of their son’s caps had been taken – the ‘good’ one.

The burning embarrassment of that moment was etched into his soul like a cattle brand, accompanied by a sound that still haunted him – his father’s cold, disparaging voice. It derided and mocked Seamus over not being man enough to stand up to a couple of fools. It told him his father wouldn’t care if he had came home minus a cap, as long as he wore a black eye or a bloodied nose as the result of an effort to retrieve it. Instead, his son had arrived home with eyes red from crying, ‘LIKE A LITTLE GIRL,’ the voice had thundered. Seamus and his mother both jumped at the clatter of his father’s knife and fork being slammed down on top of his dinner. It was done with so much force it cracked the plate. His father stood for a moment, towering over the table, casting a dark shadow across his unfinished meal. Declaring he had lost his appetite and could not spend even one more minute in the company of his own son, he stormed out of the miserable house for the consolation of the pub. If he had beaten Seamus to a pulp it would have been less painful. A lifetime later the hurt was still there, waiting to be felt at every opportunity – a legacy to pass on to the next generation.

Standing at the edge of the pier, looking into the deep murky sea, Seamus wondered why he had never learned to swim. Growing up in a harbour town, he had watched from a safe distance as his friends threw each other into the water. He was probably the only person on the island to have never stepped off it. The ferry that transported excited schoolchildren on day trips to the mainland and brought back streams of welcome tourists, had never carried Seamus. Something out there was more to be feared than anything on the island, even more frightening than his father.

A seagull screeching above his head, invaded his thoughts. As Seamus watched the circling bird a piece of paper, scooped up from the ground by a sudden gust, landed on his shoes. It looked like an envelope with an address written on it. Before Seamus could pick it up the wind tauntingly snatched it away, just as it had done with his cap. He was reminded of another letter, one that brought great sorrow to his home. It had been written some years before and filed away behind a photograph on the kitchen mantelpiece. A young man’s face smiled out from the yellowed pine frame that hid the words no parent wants to read. Seamus’s wife found the letter when she had come downstairs to make breakfast. It was resting against the teapot on the kitchen table. One thin page of accusation and dismay had turned into a thick wall of insurmountable grief, lying between them, too painful to breach.

Their only child could no longer carry the bitterness of two generations heaped upon him since childhood. His brief and poignant letter broke the news to them that he could not live with it anymore. He had decided to put an end to it once and for all. He said it broke his heart to leave his parents so suddenly and begged for their forgiveness. Those words burned themselves into his father’s heart and his mother’s soul. Seamus walked back along the pier to take a long look at his empty shop across the street. With no one to pass it on to, the family business had finally come to an end after four generations of hard work and stubborn perseverance. An overwhelming sadness swept through him. Seamus quickly turned around and, for the first time in his sorry life, stepped from the edge of the pier and off the island.

When Eileen O’Sullivan came downstairs to make the breakfast and saw an envelope standing against the teapot on the kitchen table her stomach turned. She raced back up the stairs to her son’s room, where her husband had slept the night before. Eileen had noticed something was very wrong but could not put her finger on it. She begged Seamus to see the doctor but he had refused to go, even when she eventually made the appointment herself.

Her heart pounding, the frantic woman ran back downstairs and picked up the white envelope with shaking hands. Reliving the nightmare of opening a similar envelope years before, she realized she was standing in the same spot on the kitchen floor as she had then. Eileen moved to the other side of the table as she unfolded a single page of notepaper. As she read the letter from her husband tears spilled over, splashing onto the ink and blurring the words. She wiped her eyes and shook the paper, rereading the part where he said he was sorry to leave her so abruptly, without any warning. He didn’t mean to cause her any more pain than she was already in, but it was time for him to do something. He was going to do what his son had been courageous enough to do – break the cycle of misery.

Seamus told his wife that he could no longer live in fear and regret. He would be taking the ferry to the mainland to meet up with a man who claimed to have found their son. He was going to set things right and she was to put a fresh lick of paint on the walls of her son’s bedroom. Eileen folded the letter and placed it back into the envelope. She walked over to the mantelpiece and picked up the photograph of the young man with the smiling face, holding it close to her heart. Taking the age-marked envelope that had sat for seven years behind the yellowed pine frame, she kissed it, as was her ritual every morning. She put the photo frame back on the mantelpiece and placed the letter Seamus had written behind it, with the one from their son. There was no time for breakfast, Eileen needed to get to the hardware store. She knew exactly what colour paint her boy would like in his room.

Jean Reinhardt 2014

Pingback: Short Stories for Lunch | The Writers' Workshop Blog

We are never too late to learn. Excellent story and brought me to tears. I hope the son will return and those years can be washed away with forgiving tears and embraces. I enjoyed this muchly. I thank you for finding and following my little blog. It is a bit of a mishmash but I think we have some fun. I’ve been thinking of doing a short story or two instead of my usual haiku or food post.

This has inspired me. 🙂

LikeLike

PS I forgot. I am link challenged for some reason and so am not providing the links. But if you have time and want to do the search method on my blog, I have a series of short stories in four parts – The Samurai and the Wren. It is a true story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your encouraging words. I would love to read your short story, it has a very interesting title.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sakura-san: WordPress provides the link to your blog automatically. Your name, above, becomes the link.

LikeLike

Thank you for that info!

LikeLike

Thank you for this information. It is helpful considering when I provide links for people, they are always dooooooomed!

LikeLike

Wonderfully moving story, Jean. Really enjoyed it.

LikeLike

I’m so glad you liked it, Jack, thanks for taking the time to read it.

LikeLike

An interesting concept, with a good sense of scene.

LikeLiked by 1 person

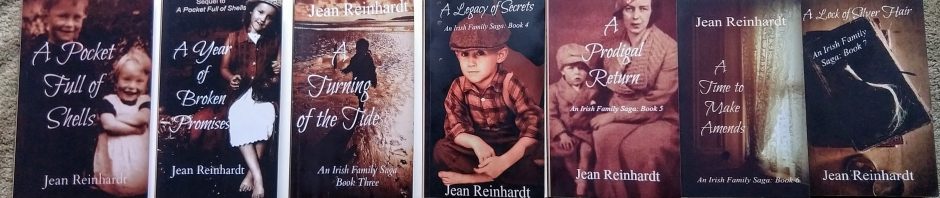

Thanks for reading it. I hadn’t written a short story in a long time. It was almost as difficult to write as any of my books, as I was restricted to a word limit.

LikeLike

An evocative story. Suppose the son had ‘left’ in the full sense? Poor wife.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s sad that some feel ending it all is the only way out for them. My story was heading that way, but I changed the outcome.

LikeLike

Story sounds so real! I enjoyed reading it. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for your comment, I’ve only just seen it now. I’m really glad you liked it.

LikeLike

very sad storie.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My mom helped me understand the ending and now I see it ends happy. I hope he comes home.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was one of my deeper stories, not based on real people but on situations that some do find themselves in. It won a competition, so I’m quite proud of this one. Thanks for your lovely comments and for taking the time to read it. I’m glad your mom explained the ending to you.

LikeLike

I love

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Didier.

LikeLike